NYC Labor market indicators register Covid-19’s ill economic effects

COVID-19 Economic Update is a bi-weekly column prepared by economist James Parrott of the Center for New York City Affairs (CNYCA) at The New School, whose research is supported by the Consortium for Worker Education and the 21st Century ILGWU Heritage Fund. Read past installments here.

Mid-January marks the 10th month since the onset of Covid-19 business restrictions. While a new Federal assistance package that continues unemployment benefits, better targets the Paycheck Protection Program, and adds another round of economic impact payments is long overdue, new Covid-19 case rates in the New York City area have been rising since October and the business and employment recovery has stalled. The January 8th national jobs report showed renewed job losses in December, especially in the leisure and hospitality sector encompassing the arts, restaurants, and hotels that have been relentlessly battered for months.

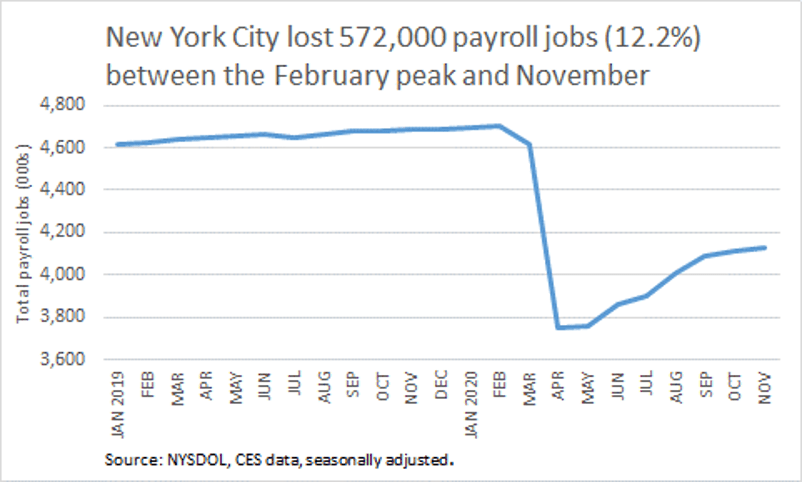

The December jobs data for New York City won’t be released until January 21st, but there’s little reason to expect good news. Here are three charts that illustrate worrisome dimensions of the city’s labor market.

In addition to the 572,000 lost payroll jobs, another 100,000 to 200,000 self-employed workers and independent contractors are still without jobs. These workers are not tracked in the monthly Labor Department employer survey. And of those working, a much higher number are working part-time because their employers are only able to offer reduced hours. There were still a million city residents receiving unemployment benefits as of mid-December, and about a quarter of them were receiving reduced benefits because they were working part-time (this compares to 10 percent of those receiving part-time unemployment benefits at the end of 2019).

The 200,000 decline in the city’s labor force over the past year is due partly to the general scarcity of job opportunities and partly because some workers are reluctant to return to work while the public health risk persists. The employment-to-population ratio (EPOP as it is known) for the city has averaged only 50 percent for the past three months, the lowest it has been since late 1992. Before Covid, the EPOP had steadily risen for more than 25 years and averaged 58 percent in 2019.

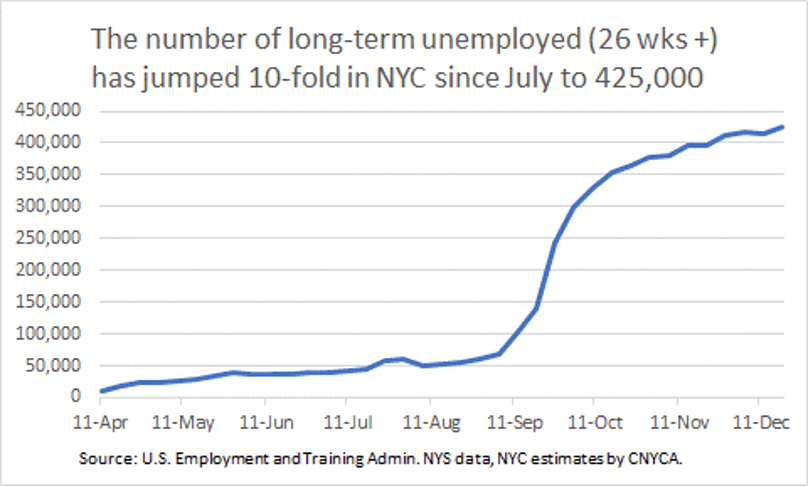

With the onset of fall, the number of city residents who had been jobless for more than six months started to climb sharply. By mid-December, the number reached at least 425,000. This number was conservatively estimated based on the number of state residents receiving extended unemployment benefits that kick in following the exhaustion of 26 weeks of regular state unemployment benefits. In addition, some number of those receiving Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA, geared to those who are self-employed, independent contractors, or otherwise not eligible for regular state unemployment benefits) have been out of work for more than 26 weeks. Between 500,000-600,000 city residents were receiving PUA benefits in mid-December. Long-term unemployment is widely recognized by economists as particularly harmful, both to the workers who go without various employee benefits, lose wage earnings, and experience reduced earnings when they are re-employed, and also to the broader economy, since it is associated with a deterioration in worker skills, productivity, and labor force attachment.