It’s clear that most of the half-million unemployed New York City workers are not jobless by choice.

COVID-19 Economic Update is a bi-weekly column prepared by economist James Parrott of the Center for New York City Affairs (CNYCA) at The New School, whose research is supported by the Consortium for Worker Education and the 21st Century ILGWU Heritage Fund. Read past installments here.

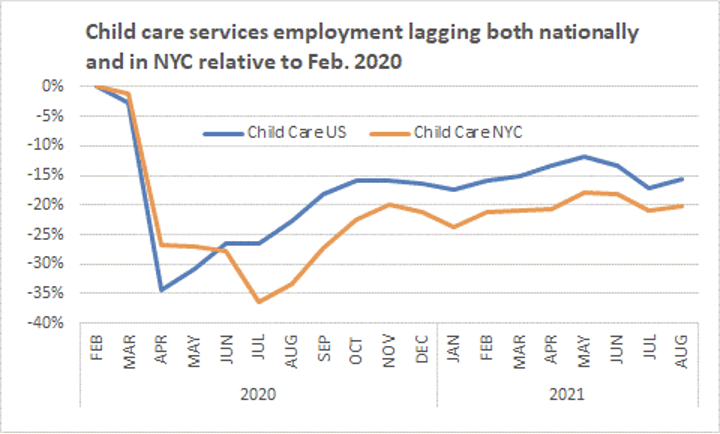

As Covid-19 infection rates have fallen in recent weeks and the economy struggles to rebound, public discourse seems to have shifted to a narrative of unemployed workers choosing to not return to jobs they previously held. Understandably, some workers are hesitant to return to work because of personal or family health concerns, and lack of good choices on child care are severe both nationally and in New York City. As of August, for example, national child care capacity, based on payroll employment, was still 16 percent below, and New York City capacity 20 percent below, pre-pandemic levels from February 2020.

Figure 1

While some still-unemployed New York City workers may not be working by choice, however, joblessness is dramatically greater here than at the national level – in fact, nearly eight times greater than in the U.S. overall. It defies logic to think that New York City workers are nearly eight times more reluctant, by choice, to return to work. Yet that is the degree to which the city’s private sector Covid-related jobs deficit exceeds the nation’s overall (-11.9 percent vs. -1.5 percent).

Patterns of job losses, and comparisons of trends in New York City and the U.S., suggest that other factors beyond individual choice are determining the extent of joblessness.

First, look at where the jobs deficit remains greatest. As of August, 85 percent of New York City’s 485,000 private jobs deficit was among predominantly low-paying face-to-face service industries and the social assistance sector that includes child care services. Workers in these industries also tend to be mostly persons of color.

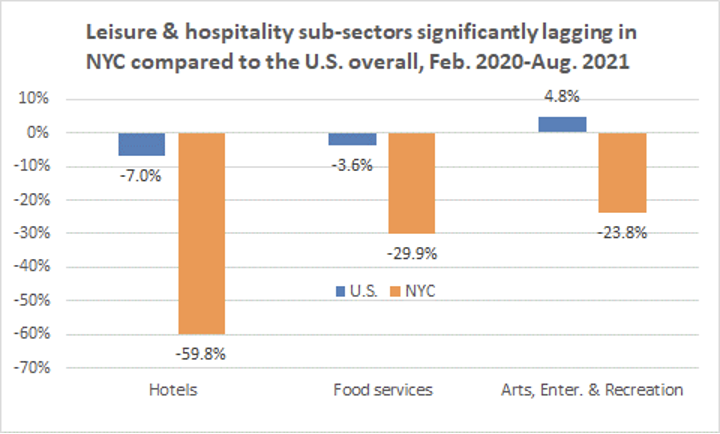

Consider the leisure and hospitality sector, the sector hardest hit by social distancing business restrictions driven by Covid-19. For the nation overall, leisure and hospitality employment dropped by more than a third in the early months of the pandemic, and by much more than that in New York City. Yet as of August of this year, even with a summer that saw arts and entertainment employment begin to recover in New York City, local job levels in this sector were still off by nearly a quarter compared to pre-pandemic levels, while national employment in leisure and hospitality was nearly five percent above February 2020 levels. New York City hotel employment was still down by 60 percent compared to February 2020, and food services employment (including restaurants and coffee shops) in the city was still 30 percent below pre-Covid levels, several times worse than in counterpart subsectors nationally.

It is indeed hard to imagine why leisure and hospitality workers would be so much more reluctant to return to work in New York City than in other cities, or why New York City hotel workers would be twice as reluctant to go back to work than local restaurant workers. This is particularly hard to understand considering that union hotel jobs in Manhattan are probably the best-paying jobs in the city for less-educated workers of color and offer much better pay and benefits than jobs in restaurants or coffee shops.

Figure 2

A similar, if less dire, pattern can be found among those employed in high-paying jobs, such as in information, financial activities, and professional and technical services. Generally speaking, they were able to continue working on a remote basis throughout the pandemic. Nonetheless, New York City employment in the remote-working group of industries saw a 6.7 percent decline as of April 2020 compared to pre-pandemic levels, and the job count was still down nearly five percent as of August of this year. On the one hand, that’s much less than the jobs hit in the face-to-face industries; on the other, a five percent jobs loss is still a severe, recession-magnitude, decline.

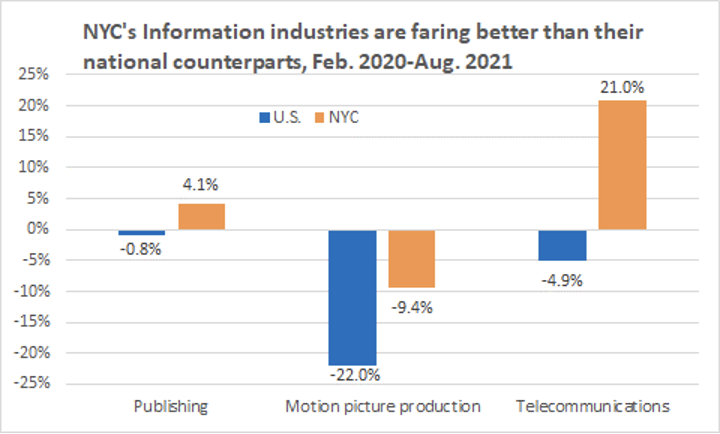

There are also strikingly uneven return-to-work patterns in such high-paying industries, both within New York City, and when comparing New York City to the U.S. For example, in the information sector, August employment numbers showed that New York City’s jobs level was 3.0 percent below February 2020, but better than the nation’s 3.9 percent shortfall. This, despite the fact that the early pandemic decline in information employment was steeper in New York City (-11 vs. -9 percent.)

Figure 3 shows that in two of the sub-sectors within information – publishing and telecommunications – August job levels were actually above pre-pandemic levels in contrast to declines for the U.S. overall. And in motion picture production, New York City’s remaining job shortfall as of August was less than half that at the national level.

Figure 3

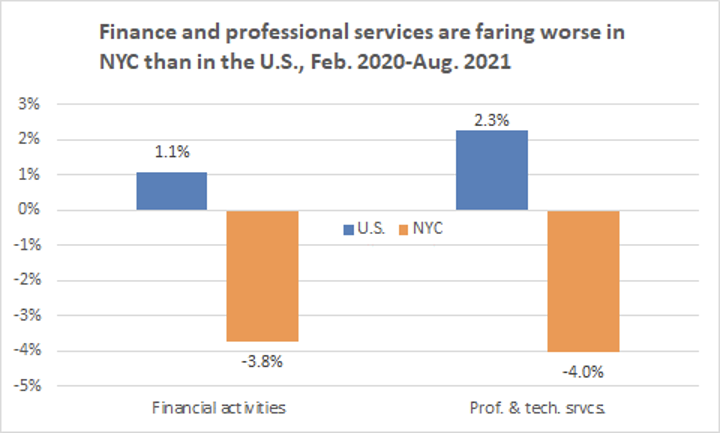

And then contrast New York City’s better-than-national jobs trend in information to that of the two other large high-paying sectors: financial activities and professional and technical services. As Figure 4 shows, in both of these sectors New York City August employment levels were still about four percent below pre-pandemic levels, while at the national level employment in both sectors now slightly surpasses pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 4

These substantially uneven patterns across both low-paying and high-paying sectors cast doubt on the notion that the majority of workers who have not returned to work remain jobless by choice. Undoubtedly, some unemployed workers are reconsidering their career choices, and that itself is positive for long-term economic growth. However, the “unemployment-is-high-mainly-because-workers-are-jobless-by-choice” narrative cannot plausibly account for much of the unemployment seen today around the country. It certainly does not apply to very many of the half-million, predominantly low-paid, unemployed New York City workers.

The more likely explanation is that differences in the lingering effects of previous business restrictions, Covid-era changes in business practices, and industry- and location-specific factors affecting business activity are playing out very unevenly, and that this unevenness accounts for the bulk of unemployment at this stage of the pandemic.

The adverse consequences of mass scale, long-term unemployment, particularly among New York City’s workers of color, should prompt a more concerted response by City and State policy makers. The jobless-by-choice narrative is trendy, but it shouldn’t be a distraction.