Rise in labor force participation pushes up the city’s unemployment rate; average weekly hours and real wages have fallen for many workers.

COVID-19 Economic Update is part of a regular biweekly Covid-19 Economic Update series. This week’s update was prepared by James Parrott, Director of Economic and Fiscal Policies at the Center for New York City Affairs at The New School. Read past installments here.

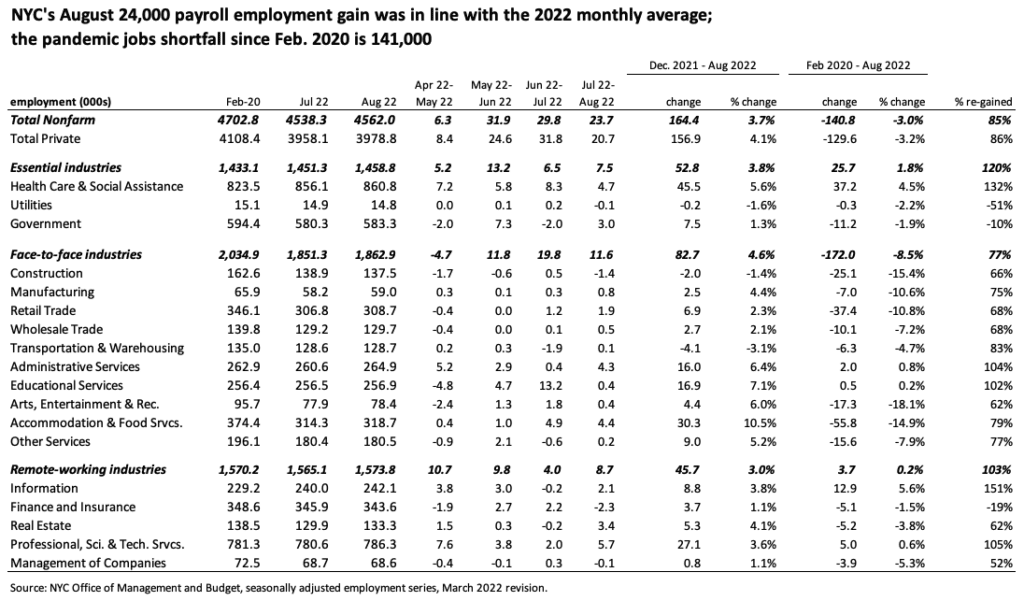

New York City gained nearly 24,000 payroll jobs in August on a seasonally adjusted basis, a pace in line with the average monthly growth so far in 2022. The city’s pandemic jobs shortfall since February of 2020 narrowed to 141,000, equivalent to three percent of the pre-pandemic job level. See the table below.

Within the face-to-face industry category, administrative services and educational services have both now reached their pre-pandemic employment levels. Within administrative services, temporary employment agency employment has more than recouped its pandemic job loss while building services employment still lags pre-pandemic levels.

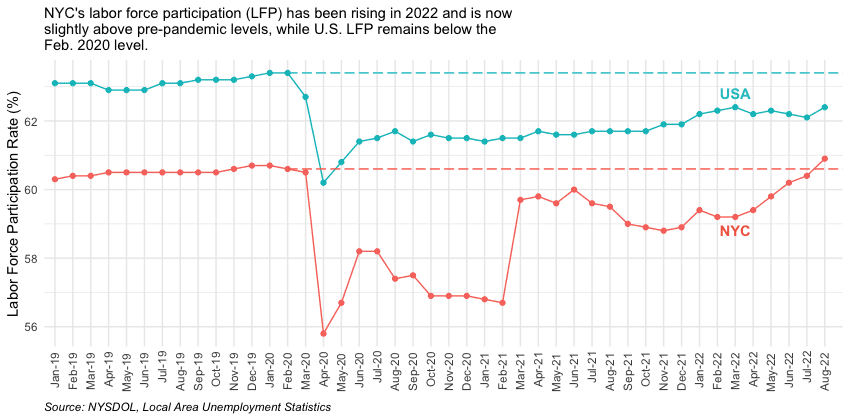

The big story from the August employment data release was the sharp uptick in New York City’s unemployment rate, rising from six percent in July to 6.6 percent in August. This resulted not from layoffs, but from an influx of job seekers into the labor force, raising the city’s labor force participation rate to 60.9 percent, slightly above the pre-pandemic level of 60.6 percent and the highest monthly level in over 10 years. The chart below shows a steady rise in labor force participation in New York City this year compared to a very gradual rise for the nation overall.

The steady rise in labor force participation is challenging to square with anecdotal reports from employers about difficulty filling job openings in many entry-level fields, although the picture is complicated by the fact that the size of the city’s overall labor force remains 272,000 below the pre-pandemic level. Still, the fact that there are 108,000 more New Yorkers unemployed and seeking jobs than before the pandemic suggests a jobs shortfall rather than a dearth of job seekers.

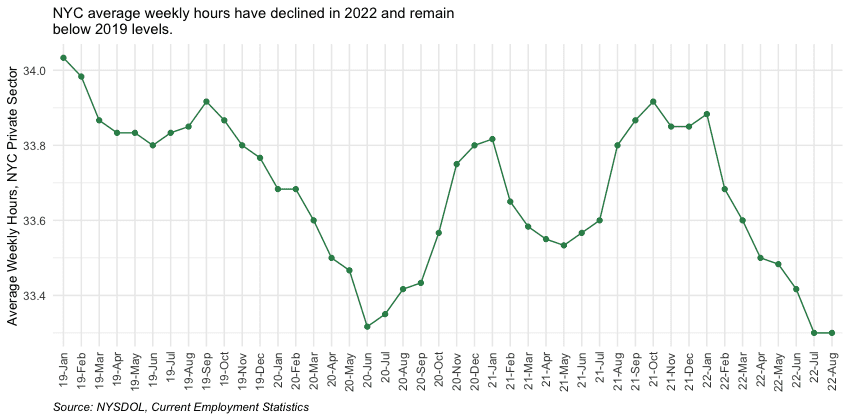

Another indicator that appears at odds with a labor shortage situation is that average weekly hours worked in the city’s private economy have declined throughout 2022 and remain below 2019 levels, as the chart below indicates.

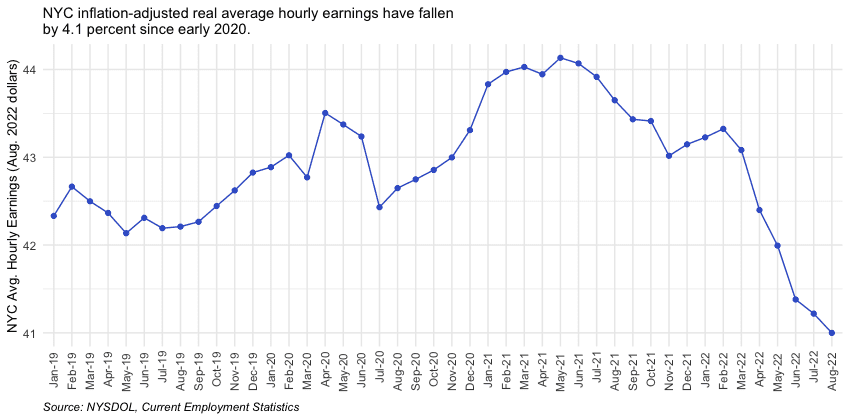

If businesses were experiencing difficulty filling vacant positions, employers would be expected to press existing workers to work additional hours. Moreover, businesses would respond to a serious worker shortage with higher wage offers. Yet, inflation-adjusted average hourly earnings have fallen by 4.1 percent since early 2020. See the graph below.

Granted, most of this decline in real earnings results from the highest inflation in several decades, and employers not able or willing to raise wage offers may be the ones experiencing the greatest hiring challenges. The sharp rise in private average hourly earnings in early 2021 likely reflects a mixed effect given the loss of several hundred thousand (mainly low-paying) jobs at that point, and some of the drop-off in recent months may reflect the fact that many low-paying jobs were restored, a fact that by itself would lower the average.

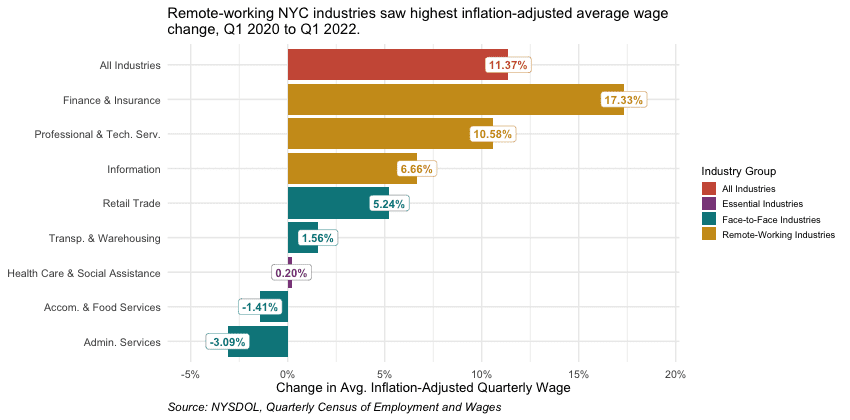

A separate data set from the State Labor Department data set allows us to look at the change in inflation-adjusted average pay on an industry basis. The Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, based on administrative data compiled for the payment of unemployment insurance payroll taxes, shows a wide disparity in the average wage change between high- and lower-paying industries in New York City. The final chart below shows an 11.4 percent increase in average wages across all sectors of the city’s economy between the first quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2022 (the latest period for these data). While average wages rose by 17.3 percent in the finance sector and by 10.6 percent in professional services, inflation-adjusted average wages fell by 3.1 percent in administrative services and by 1.4 percent in accommodation and food services. The small 0.2 percent wage gain in the health care and social assistance sector partly results from the continued rapid growth in very low-paying home health care jobs, which now constitute nearly 29 percent of all jobs in health care and social assistance.